PHILADELPHIA’S LUXURIOUS LIBRARY

Photograph taken by the author on October 3, 2019

The Athenaeum of Philadelphia

219 South 6th Street, Philadelphia, PA 19106

William Ross

December 4, 2019

Abstract:

The Athenaeum of Philadelphia is a membership-based private library that was created in 1814 in order to provide access and storage for useful information. The process of selecting and modifying the design and construction of the Athenaeum’s building, completed in 1847, is a historical example of successfully navigating between cost-effectiveness and fashionable aesthetics in architecture within the larger context of relevant historical events and precedents. For this research, scholarly publications were reviewed and compared. An interview and building tour was also conducted with the Athenaeum’s Curator of Architecture on this subject. This paper will explore how economics, other institutions, personal connections, design precedents, and innovations culminated in the Athenaeum building that exists today. This paper offers a deeper understanding about the origins of the Athenaeum building that may enrich the reader’s knowledge base should he or she encounter similar projects in the future.

Leading into the turn of the 19th Century, Philadelphia grew in prominence. As a result, Philadelphians needed places to access and store printed information. The Athenaeum of Philadelphia, a private member-supported library, was one of many institutions that emerged to meet this growing need. However, the founders of the Athenaeum envisioned their library lasting into the future. In order to realize that vision, building committees explored fiscally responsible methods of procuring a permanent location, including attempts at multi-institutional collaboration. When collaboration was no longer viable, the Athenaeum focused on finding its’ own cost-effective, long-term building. National and local economic events, however, undermined these initial efforts. Although many Architects submitted proposals, often preemptively due to the bad economy, the Athenaeum’s limited budget ensured only the most affordable plans were considered. At the same time, a desire for a fashionable building made selecting a plan difficult. The architect whose design was finally chosen used many tricks to beautify the building while keeping costs low. His design also ensured the Athenaeum had rental income in perpetuity. As a result, the second floor became the center of the Athenaeum’s library. Precipitating from all this planning, the Athenaeum continues today. The building of the Athenaeum of Philadelphia resulted from a quest to find a cost-effective and fashionable long term meeting place for members to access and store the institution’s written publications.

The Athenaeum of Philadelphia was born out of a community need. During the early 19th century the only means of gathering or accessing information was through physical institutions dedicated to that purpose and supported by paying members (Breisch et al, 14). In Philadelphia, there were two waves of institutions created to fulfil this essential purpose: The first wave included the Library Company created by Benjamin Franklin, the Loganian Library, and the Carpenter’s Company (Bruce Laverty). The second wave included the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in 1805 and The Academy of Natural Sciences in 1812 (Bruce Laverty). It was during this era that, in 1814, the Athenaeum of Philadelphia was born (Moss, Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia).

When the Athenaeum was founded, it had several purposes. It’s first goal (Mission and History) was “…collecting periodicals, maps, dictionaries, and books of reference ‘to disseminate useful knowledge’ ” (Moss, American Membership Libraries, 132). It’s other goal was to provide a physical space for people to access those materials (Greiff, 99). This need for physical space spurred later developments.

The founders of the Athenaeum intended for the institution to exist long term which necessitated that it should eventually find a permanent location. Starting in 1814, the Athenaeum moved between rented rooms while looking for stability. After briefly renting the second floor of a building on Chestnut Street that was soon sold and demolished (Moss, Philadelphia Victorian, 8), the institution rented two rooms in the American Philosophical Society or “APS” Hall (Kennedy, 260). From 1817 until 1845, the Athenaeum became a long-term tenant at the APS Hall while the board of directors continually explored new opportunities for more permanent accommodations over the decades.

The Athenaeum explored many cost effective options on its’ quest for a permanent location. The main criteria used on this search entailed that the new building should be practical, accessible, and affordable (Moss, Philadelphia Victorian, xi). One of the earliest attempts at meeting all three of these criteria was the failed bid to purchase Surgeon’s Hall (Moss, Philadelphia Victorian, 9). However, a new opportunity arose a few years later.

The possibility of cost-effective multi-institutional collaboration emerged when a large city site opened up for development. In 1836, the massive Walnut Street Prison was demolished. This prison complex spanned almost the entire length of Washington Square. Many Philadelphia institutions began eyeing this valuable real estate.

A series of failed attempts at institutional collaboration city wide ensued. One of the most ambitious and unusual surviving designs is Thomas Somerville Stewart’s Egyptian Revival project. It would have spanned 314 feet by 132 feet (Moss, Philadelphia Victorian, 22). Another design submitted was William Strickland’s rectangular plan surrounding a large court (Moss, Philadelphia Victorian, 22). In both projects, the collaborators included the Mercantile Library, Library Company, Academy of Natural Sciences, Foreign Language Library, The Law Academy, and the Athenaeum of Philadelphia (Moss, Philadelphia Victorian, 21). The number of participants would have ensured that the project was more economical than the construction of individual structures could be. It would have also made it very convenient for members to access all these institutions under one roof. However promising, these plans fell through.

After collaboration was aborted, the Athenaeum reverted back to the original search for its’ own cost-effective, long-term location. From 1839 to 1845, the Athenaeum held Architectural competitions for the construction of a permanent Athenaeum building: “In 1839, yet another committee - consisting of Messrs. Samuel Norris, Quintin Campbell, and John C. Montgomery - invited architects of the city to submit designs for ‘a chaste and classical edifice for the more secure and permanent accommodation of the institution with its accumulating treasures’ “ (Moss, Philadelphia Victorian, 27). The two requirements at this point, according to Bruce Laverty, was to have a building that was (1) cheap, and (2) would pay for itself forever. It was determined that this could be accomplished by having rent paying tenants (Bruce Laverty).

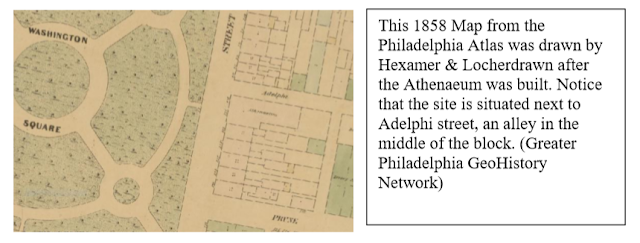

Economic events intensified the Athenaeum’s budget-consciousness. The panic of 1837, inculcated by Andrew Jackson’s bank wars, resulted in a depression (Moss, American Membership Libraries, 133). As a result, the City of Philadelphia defaulted on $600,000 interest on bonds (Moss, Philadelphia Victorian 49). Due to the nature of these events, the Athenaeum renewed its lease with American Philosophical Society for three more years and put acquiring a site and construction on hold (Moss, Philadelphia Victorian, 49). For this reason an auspicious site on 6th and Walnut remaining vacant (Moss, Philadelphia Victorian, 27) but the Athenaeum eventually chose a cheaper site. Nearly a decade later, on February 24, 1845, the Athenaeum purchased a 50 feet x 120 feet building site at Sixth and Adelphi Streets for $18,000 (Greiff, 100).

The Curator of Architecture Bruce Laverty points out that Athenaeum members immediately started asking “Why such a remote site?” (Laverty) The simple answer was that they bought the land cheap (Bruce Laverty).

This new level of budget-consciousness also played a role on what architectural plans would be considered for the Athenaeum building. An Athenaeum member named Dr. Lehman had died and bequeathed $10,000 in 1829 (Moss, Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia) to the Athenaeum for the construction of a permanent building (Moss, Philadelphia Victorian, 86). The amount grew to $24,000 (Moss, Philadelphia Victorian, 86). This number was so strictly adhered to that “...the directors left it to the [building] committee ‘to contract the erection of a building on either of the above reported plans,’ so long as it came in under the $24,000 limit” (Moss, Philadelphia Victorian, 83).

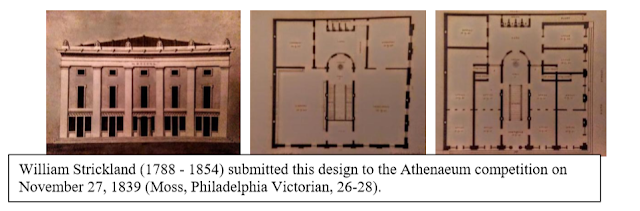

Many architects offered designs for the competition. Some architects even submitted preemptively due to the lack of work because of the depressed economy (Moss, Introduction, iv). Architects as notable as Strickland, Walter, Haviland, and LeBrun all submitted designs.

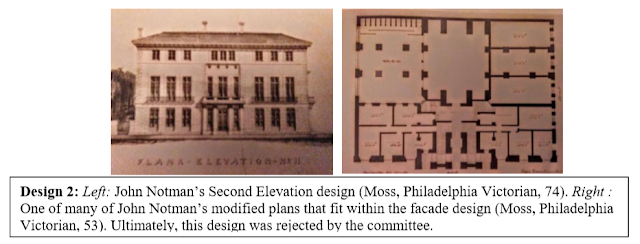

However, it was board member John Montgomery who brought the aspiring young architect John Notman to the Athenaeum building committee’s attention. Notman’s father, David, had worked at Fernieside quarry near Edinburgh Scotland (Greiff 15) where John was born (Tatman, Philadelphia Buildings). John Notman then apprenticed as a carpenter (Greiff 16) and worked for the architect William Henry Playfair (Grieff 16) before emigrating to Philadelphia (Tatman, Philadelphia Buildings) where he eventually became an architect himself (Grieff 18). Stylistically, Notman was particularly inspired by Charles Barry’s Traveller’s Club (Moss, Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia), a building that introduced Italianate revival to England.

Balancing the desire for a cost-effective and fashionable long term building made the Athenaeum’s building committee very hard to please. Despite the economic limitations, the committee continued to adhere to their original quest that the Athenaeum should be “the pride and ornament of Philadelphia” (Kennedy, 262). Notman furnished four designs before his fifth design was accepted. Each drawing illustrates well the progression of designs Notman developed in an effort to please the building committee’s tastes and budget.

It was Notman’s fifth design that the committee finally agreed was a “ ‘sufficient size, and with sufficient means of light, air, at a reasonable price’ “ (Moss, Philadelphia Victorian, 56). Most importantly, it adhered to the $24,000 limit on construction costs imposed by the board. The building was finally completed in 1847 (Breisch et. al, 49).

Notman’s design used many tricks to reduce cost while appearing fashionable. First, an Italianate building with “classical bells and whistles” is not as expensive to build as other styles (Laverty) Next, the extensive use of cheaper materials reduced costs and work time (Laverty). Even though the exterior was originally meant to be marble, brownstone was used (Greiff, 101). The Curator of Architecture Bruce Laverty notes that it was cheaper to carve the brownstone used on the facade.

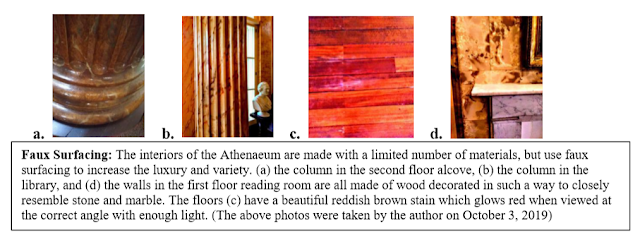

On the interior, surfaces are masked in faux, making them stylistically appealing while adhering to the budget. For example, pine wood work and cheap wood flooring was stained to look expensive (Laverty). While visiting the Athenaeum, I observed that the interior columns are painted to look like marble while actually being made of wood, further reducing costs.

Interestingly, the Corinthian column capitals in the library and newspaper room are made of “Compo,” a recycled material composed of horse hair, plaster, and wool held in shape using wire (Laverty). This method reduced work time and costs to make all the capitals (Laverty).

Another important feature of Notman’s design was that it would supply long term income for the Athenaeum. Six rentable offices and a lecture hall with a flat floor that could be rented out (Greiff 101) were executed on the ground floor, while nine rentable offices were planned on the third floor (Moss, American Membership Libraries,135)

Office space was rented to stock brokers, lawyers, insurance companies, shipping companies, and others (Bruce Laverty). This ensured that the Athenaeum would remained solvent long term.

The second floor library was designed to be the fashionable locus of the Athenaeum. With a colonnade reaching up to 24 foot high ceilings in a large, bright area, there is no question that this space was built to impress. The Curator of Architecture Bruce Laverty explains it beautifully: “The library room was designed for the enjoyment of the printed word on the real page. The space quiets people, it brings reflection, inspiration. It provides the space needed for the sacred transfer of knowledge and entertainment” (Laverty).

Today, the Athenaeum building continues its’ long term splendor and function as a library and a fashionable building. It is thanks to preservation (More Color Sources) and reinforcement efforts in the 1970s (Survey Reveals Serious Structural Problems) and in the 1990s (Hine, Inquirer) that the Athenaeum building continues to exist long term. Below are some examples of many of the Athenaeum’s elegant architectural features visible today.

The Athenaeum of Philadelphia building became the cost-effective and fashionable long term meeting, access, and storage place its’ founders had imagined. Because of this careful and visionary preparation, the Athenaeum continues today and into the future. The second floor remains the focus of the Athenaeum’s library collection. Rental income over the years helped keep the Athenaeum solvent over time. The beautifying tricks and innovations that arose originally from budgeting have engendered continued interest in the space. This successful building and institution is the legacy of careful architectural selection balanced against a hard budget complicated by national and local economic issues. Interestingly, this beautiful building would not exist had multi-institutional collaboration succeeded. The Athenaeum founders envisioned a library lasting well into the foreseeable future, and it continues to support the needs of Philadelphians and foreigners alike as a place for the access and storage of information. Even more significantly, in a busy digital world, it remains an enchanting place dedicated to something timeless: people and books.

Work Cited

Breisch, Kenneth, and Carla Hayden. American Libraries 1730-1950. W.N. Norton & Company, 2017, pp. 13–27, 49.

Greiff, Constance M. John Notman, Architect, 1810-1865. First ed., Athenaeum of Philadelphia, 1979.

Greater Philadelphia GeoHistory Network, 2019. http://www.philageohistory.org

Hine, Thomas. “The Renewal of the Athenaeum.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 3 Jan. 1993.

“Historic American Buildings Survey: Philadelphia Athenaeum" Prints; Digital Online Catalog, Library of Congress, 1999, www.loc.gov/pictures/item/pa1092.sheet.00001a/.

Kennedy, Arthur M. “The Athenaeum. Some Account of Its History from 1814 to 1850.” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 43, no. 1, 1953, pp. 260–265. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1005679.

Laverty, Bruce. Personal interview. 11 November 2019.

“Mission and History.” The Athenaeum of Philadelphia, www.philaathenaeum.org/.

“More Color Sources.” Athenaeum Annotations. Athenaeum of Philadelphia, 1979.

Moss, Roger W. “Dear Athenaeum Member.” Athenaeum of Philadelphia, East Washington Square: November 1, 1989.

Moss, Roger W. “Introduction.” Catalog of Architectural Drawings, GK Hall & Co, 1986.

Moss, Roger W. Philadelphia Victorian: the Building of the Athenaeum. First ed., Athenaeum of Philadelphia, The Athenaeum of Philadelphia, 1998.

Moss, Roger. “The Athenaeum of Philadelphia, Est. 1814.” American Membership Libraries, First ed., Oak Knoll Press, 2007, pp. 131–155.

Moss, Roger W. “The View From Washington Square.” Athenaeum Annotations. Athenaeum of Philadelphia, 1991.

Moss, Roger. “Athenaeum of Philadelphia,” Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, Rutgers University, 2015.

https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/athenaeum-of-philadelphia/.

“Survey Reveals Serious Structural Problems.” Athenaeum Annotations. Athenaeum of Philadelphia, 1991.

“The Handsomest Edifice.” Philadelphia Bulletin, 17 Dec. 1978.

Tatman, Sandra L. “Notman, John (1810-1865).” Philadelphia Architects and Buildings, https://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/ar_display.cfm/26273/.

Weigley, Russell F., et al. Philadelphia: A 300 Year History. W.W. Norton, New York, 1982, pp. 242-243, 314-315.

“Welcomes You to the Nineteenth Century.” The Athenaeum of Philadelphia, 1973.

No comments:

Post a Comment