Andrea Palladio, the Villa

Rotunda,

And the rise of Palladianism

William Ross

November 4, 2019

Andrea Palladio

rose from humble origins to become one of the greatest Architects of all time.

Palladio was born at a time when Renaissance Humanism was rediscovering the

accomplishments of the ancient Greeks and Romans, and using this new knowledge

to challenge the status quo of religious, medieval European thinking. Many of

Palladio’s later accomplishments were made possible by the work of previous

generations in the Renaissance Humanist movement who had rediscovered and

reinterpreted Vitruvius and various elements of ancient art, perspective, and

engineering. Palladio was born into this auspicious era of creativity and

exploration, but it was only because of a chance encounter with a humanist

scholar named Trissino that Palladio was able to participate in these

developments. Given the opportunity to learn by Trissino, Palladio took his

education seriously. He read Vitruvius’ works, he studied ancient Roman

buildings, and he used those observations and measurements to evolve his own

architectural designs in a quest for beauty and perfection. Throughout a

lifetime of study, Palladio merged practice and theory to create the perennial

design of the Villa Rotunda and to write his seminal masterpiece The Four

Books of Architecture. Both of these major lifetime accomplishments created

a legacy that inspired future designers like Indigo Jones and generations of

architects to the present day. Building on the work of previous generations and

the architectural achievements of Ancient Rome, Andrea Palladio fundamentally

revolutionized architecture for future generations world-wide by discovering

aesthetics for modern life.

During the 13th, 14th, and 15th

centuries, a philosophical revolution was taking place across the Italian city

states. Studia humanitatis, or “Renaissance Humanism,” was emerging as a

temporal challenge to the religious mind set of the middle ages (Wilde). These

humanist scholars scoured Europe in search of surviving ancient Roman and Greek

texts, knowledge, and understanding. However, they were persecuted by the all-powerful

Roman Catholic church throughout the 13th century because of the

threat they posed to the medieval social order: “Renaissance Humanism was using

the study of classical texts to alter contemporary thinking, breaking with the

medieval mindset and creating something new” (Wilde, A Guide to Renaissance

Humanism). Because of this challenge, Humanist ideas could only spread

slowly, gradually, and rarely reached or changed the beliefs of those in power.

However, a single man, the fourteenth century poet Francesco Petrarch (1303 -

1374), changed all that.

Petrarch

transformed Renaissance Humanism from a fringe academic movement into a

powerful force. By working “at bringing together the classics and the

Christians” (Wilde), he created his “Humanist Program” (Wilde) which brought in

new thinkers like the powerful chancellor of Florence, Coluccio Salutati

(Wilde). With newly found acceptance among European elites, Renaissance

Humanism spread rapidly across Italy and into the rest of Europe: “By the

mid-15th century, Humanism education was normal in upper-class Italy” (Wilde).

Soon any field that required literacy was dominated by Humanists (Wilde).

Because of this situation, the famous author, art theorist, and architect Leon

Battista Alberti (1404 - 1472) was given a humanist education.

Alberti was an

extensive writer whose work had a lasting effect on Renaissance thought. As the

child of a wealthy merchant family in Florence (Kelly-Gadol), Alberti received

a proper humanist education in Padua and later at the University of Bologna

(Kelly-Gadol). He mastered Latin and wrote about geometry, geography (with

Paolo Toscanelli), art, perspective, and moral philosophy (Kelly-Gadol).

However, his most significant accomplishment arose when he was employed by

Marchese Leonello at the Este court in Ferrara to restore Vitruvius’ seminal

work The Ten Books of Architecture. His translation and elaboration on

Vitruvius, De Re Aedificatoria: “won him his reputation as the

‘Florentine Vitruvius.’ It became a bible of Renaissance architecture, for it

incorporated and made advances upon the engineering knowledge of antiquity, and

it grounded the stylistic principals of classical art in a fully developed

aesthetic theory of proportionality and harmony” (Kelly-Gadol). De Re

Aedificatoria brought Vitruvius up to date during Renaissance Italy,

spreading ancient Roman architectural ideas far and wide.

De Re Aedificatoria heavily influenced

Andrea Palladio’s mentors and contemporaries. The mannerist architect Sebastian

Serlio (1475 - 1554) used De Re Aedificatoria as an aid in his study of

ancient Roman Architecture (The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica) while

writing his own book Tutte l’Opere d’Architettura, et Prospetiva. Later,

Andrea Palladio would write about how much Serlio’s treatise had inspired him

(Placzek) and it had visible influences on his design for the Vicenza town hall

(Richardson). The mannerist architect

Giacomo da Vignola (1507 - 1573), another of Palladio’s contemporaries, also

heavily relied on De Re Aedificatoria to create the Churches of St.

Andrea and Il Gesu as well as to write his own book Regola Delli Cinque

Ordini d’Architettura in 1562 (The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica). The

Vitruvian climate of Architectural thought undoubtedly exerted an enormous

influence on Andrea Palladio, who considered Vitruvius to be “his master and

guide” (Richardson). It was out of this

Renaissance Humanist ethos that Palladio rose to accomplish some of his most

significant work.

Andrea’s life was

marked by struggles and chance occurrences that make his accomplishments seem

even more extraordinary. Andrea Palladio was born in the town of Padua in

Veneto (modern day Italy) to a poor and illiterate father named Pietro. During

the first 16 years of his life he was apprenticed to a sculptor before joining

a guild of brick layers and stonemason’s in Vicenza (Richardson). As he grew

older, he worked as an illiterate sculptor and day laborer for various

construction crews in the region through the guild. One project, however, would

change the direction of his life forever.

The humanist scholar Count Giorgio Trissino

(1478 - 1550) was renovating his villa, and Palladio happened to be a member of

the crew working on the project. Through a chance encounter, Trissino met

Palladio and, for one reason or another, took Palladio in like his own son. He

began giving Palladio a humanist education in literacy, mathematics, music,

philosophy, and the ancient classics (Richardson). It was through Trissino that

Palladio met the famous contemporary architect Sebastian Serlio (Richardson)

and read De Re Aedificatoria, thereby learning about Vitruvius. However,

the most significant events in Palladio’s education were his trips to Rome with

Trissino in 1541 and in 1547. It was through these trips that Palladio gained

first-hand experience of ancient Roman and contemporary Renaissance

architecture (Richardson) and began to develop his own Architectural ideas.

For the first

time, Palladio began creating his own Architectural designs. His very first

design was the Villa Lonedo which was followed by the Palazzo Civena

(Richardson). After returning from his second trip to Rome, Palladio won the

competition to reconstruct the Vicenza town hall in 1548 (Richardson), an

accomplishment that helped spread his fame across the region (Cram). For the

next seven years, Palladio worked tirelessly on a slew of new architectural

projects for an ever increasing number of clients who competed for his services

(Cram). However, Palladio’s education was not finished.

In 1554, Palladio

abruptly stopped working on new commissions despite the ever increasing demand

for his services. Instead, he went to Rome where he remained for the next two

years tirelessly studying, measuring, and analyzing ancient Roman buildings. For

Palladio, one of the most significant ancient buildings he studied was the

Pantheon:

The amount of space Palladio

dedicates to the Pantheon in his later treatise The Four Books of

Architecture belies its’ significance for him. It is the only building in

his work with an illustration that takes up two whole sheets of paper. It also

has one of the most lengthy and glowing descriptions in his fourth book. He

begins his description by stating: “Among all the temples that are to be seen

in Rome, I celebrate none more than the Pantheon, now called the Ritonda,

nor [are] the remains more entire; since it is to be seen almost in its

first state as a fabric…” (Palladio 99’ transl. Isaac Ware). The shape and

components of the Pantheon would appear in Palladio’s later architectural

accomplishments.

Following a theme

in architectural design, Palladio puts emphasis on a second and equally

significant building: Bramante’s Tempietto built for Pope Julius II (Bruschi).

Interestingly, this is the only contemporary sacred space included in

Palladio’s fourth book.

One possible reason for this inclusion

may be because of Bramante’s faithfulness to the classical design principals as

Palladio understood them: “Bramante became the interpreter, in architecture and

city planning, of the pontiff’s dream of re-creating the ancient empire of the

Caesars. Bramante planned gigantic building complexes that adhered as never

before to the idiom of antiquity.” (Bruschi). The imperial renovations of Rome

that had taken place around the time of Palladio’s birth must have enabled the

first ever contemporary use of true classical principals in contemporary

building.

When Andrea

Palladio returned to Viscenza, he set about creating his most unusual and most

influential villa: the Villa Rotunda. The Villa Almerico Capra Valmarana, built

it 1571 and commonly known as the Villa Rotunda, is possibly the most

significant building Palladio ever built.

The Villa Rotunda, according to the

UNESCO World Heritage Sites, is “a unique survival of a total humanist concept

based on a living interpretation of antiquity” (UNESCO World Heritage Center).

Among Palladio’s significant achievements in this design is a hierarchy of

spaces, proportion, paths, balance, areas for different functions, and sources

of natural lighting and ventilation (Functional Analysis). Overall, the villa

appears to be a culmination of Palladio’s humanist education, architectural

experience, and has obvious connections with the Pantheon and Bramante’s

Tempietto:

After the grandeur

of the Roman empire began to decline, through the continual inundations of the

Barbarians, architecture, as well as all the other arts and sciences, left its

first beauty and eloquence, and grew gradually worse, till there scarce

remained any memory of beautiful proportions, and of the ornamented manner of

building, and it was reduced to the lowest pitch that could be.

But, because (all

human things being in perpetual motion) it happens that they at onc time rise

to the summit of their perfection, and at another fall to the extremity of

imperfection; architecture in the times of our fathers and grandfathers,

breaking out of the darkness in which it had been for a long time buried, began

to show itself once more to the world. (Palladio 97, transl. Isaac Ware)

This building’s form appears to be an

embodiment of this revolutionary attitude. It is an innovation on all of

Palladio’s previous designs. As seen by the Villa Rotunda’s significance in

ensuing centuries, it may even be the defining moment that elevated Palladio’s

work above his contemporaries and helped create something totally new and a

lasting legacy: Palladianism.

Palladianism

became a revolutionary new way to design. It promoted clarity, order, symmetry,

and connection with the past (Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica), all of which

was at odds with the earlier Mannerist and later baroque styles of

Architecture. Essentially, it was, and still is, Renaissance Humanist values

encoded in the architectural design of a building: “Palladianism is the

conviction, first of all, that a universal applicable vocabulary of

architectural forms is both desirable and possible; secondly, that such a

vocabulary had been developed by the ancient Romans, and thirdly, that a

careful and judicious use of these forms will result in beauty” (Placzek, v.).

In this way, beauty was intrinsically linked with good architecture for

Palladio.

As much as

Palladianism is a way to design, it is also a conscious decision about what is

important about buildings and architecture. It is the idea that buildings

should be a practical joy. This can be seen by Palladio’s innovative and

systematical approach to the plan of a house (Richardson) as well as the use of

“the ancient Greco-Roman temple front as a portico” on a private residence

(Richardson). In this way, Palladianism

exemplifies the idea that the content of the architecture is more important

than the form.

Tragedy struck at

the end of Andrea Palladio’s life, but his pupil Vincenzo Scamozzi ensured

Palladianism would continue. One of Palladio’s sons was convicted of murder and

was sentenced to death (Cram). His other son died in an accident (Cram). Unable

to cope with the grief from these tragedies, Palladio became a recluse and

isolated himself (Richardson). This became Palladio’s final struggle at the end

of his life. In a kind of sad irony, the man who would become one of the most

influential and famous architects of all time, died as an isolated spendthrift

in August of 1580 (Cram). However, Scamozzi ensured that many of Palladio’s

unfinished buildings were completed posthumously. Continuing construction

ensured that Palladianism would continue on in Viscenza.

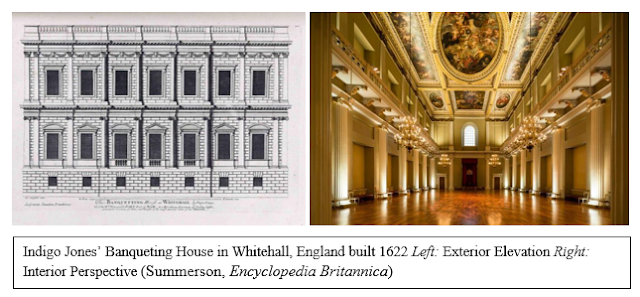

Palladianism was

brought to England and popularized for the rest of the European world through

an unlikely source. Indigo Jones (1573 – 1652) was the son of cloth worker and

over his lifetime he became a jack of all trades and an opportunistic social climber

(Summerson). At different times during his varied life he learned painting;

designed costumes, stage sets, and props; and was a land surveyor. However, he

stepped into the lens of history when he visited Italy in 1613 with the second

Earl of Arundel, Thomas Howard (Summerson). During this visit, Jones acquired a

copy of The Four Books of Architecture and began educating himself about

Architecture. When Jones returned to England, an opportunity to show off

his new skill arose when a fire destroyed a banqueting hall in Whitehall in

1619 (Summerson). Jones seized the opportunity and designed the Banqueting

House using many of the principals of Palladianism developed by Andrea

Palladio.

The Banqueting House popularized

Palladianism in Britain. At this time, members of the Whig party in England

were looking for a new architectural style (Editors of Encyclopedia

Britannica). Under these influences, soon many architects were exploring and designing

Palladian buildings.

The Villa Rotunda seems to be one of Palladio’s most lasting legacies. The Villa was the inspiration for many buildings throughout the 18th century. One of the earliest reinventions of Palladio’s seminal work was the Cheswick House, built in 1729 and designed by the wealthy 3rd Earl of Burlington, Richard Boyle (The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica).

Another estate that draws inspiration

from the Villa Rotunda is Holkam Hall in Norfolk, England. William Kent was

Richard Boyle’s student (Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica), and likely

learned about Palladianism from Boyle.

Across the Atlantic, Thomas Jefferson

drew inspiration from the Villa Rotunda when he began designing Monticello in

1772. The style’s crossing of the Atlantic to North America makes sense because

of the British colonial influences: “Naturally, the Georgian architecture of

the United States develops directly from Palladio through the later masters who

followed Inigo Jones” (Adams). It was after Jefferson visited Europe and

encountered true Palladianism that he developed the final design below:

Palladio continues

to wield a strong contemporary influence in the 21 Century. Today, some

Architects continue to design Palladian buildings using the revolutionary and

worthwhile ideas about beauty developed by Palladio. The merit of Palladio’s

remarkable legacy is highlighted by the fact that architects have continued to

draw inspiration from his work for over 500 years.

In the United States,

RAMSA Architects completed a new Palladian style admissions center for Elon

University in North Carolina. There are many recognizable Palladian elements in

the design, as well as a rotunda that is suggestive of Palladio’s Villa Rotunda

(Traditional Building Magazine).

In England,

Quinlan and Francis Terry Architects design breathtaking Palladian

architecture: “Even today, there are

Architects, notably the father and son team Quinlan and Francis Terry, who

continue to work in a tradition descended from Palladio” (Glancey, Guardian

Newspaper). These buildings draw inspiration from many of the earlier designs

done by Palladio:

Andrea Palladio’s

ideas and legacy have had a lasting impact on the world. Palladio made major contributions to the

field of Architecture. He was inspired by ancient Roman buildings like the

Parthenon and contemporary buildings like Bramante’s Tempietto, but he

developed these forms further. Palladio’s Villa Rotunda led to the Palladian

Style. It has been reinvented and a source of inspiration for many generations.

The Four Books of Architecture contain measurements, proportion, and

relationships between the parts of Ancient buildings still in use to this day.

His ideas and innovations, once geographically isolated, have spread world-wide

through the work of people like Indigo Jones. Palladio has made a lasting mark

on Architectural history and that legacy continues to the present. Today,

architectural firms like Quinlan and Francis Terry and RAMSA continue to build

Palladian buildings inspired by Palladio’s immense and transformational legacy.

Andrea Palladio was not born into greatness. He worked tirelessly all his life

to find the key to beauty. The man who started out as the poor, illiterate

stone cutter became the architect that changed the world.

Work Cited

Andrea

Palladio, https://www.nndb.com/people/828/000084576/. “Andrea

Palladio.” The Morgan Library & Museum, 11 Mar. 2016, https://www.themorgan.org/exhibitions/online/Renaissance-Venice/Andrea-Palladio.

Britain

Express. “Holkham Hall: Historic Norfolk Guide.” Britain Express, https://www.britainexpress.com/counties/norfolk/houses/holkham.htm.

Bruschi, Arnaldo. “Donato

Bramante.” Encyclopædia Britannica,

Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 7

Apr. 2019, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Donato-Bramante.

Cartwright,

Mark. "Vitruvius." Ancient

History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia, 22 Apr 2015. 30 Oct 2019.

Centre,

UNESCO World Heritage. “City of Vicenza and the Palladian Villas of the

Veneto.” UNESCO World Heritage Centre,

https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/712/.

Cram,

Ralph Adams. "Andrea Palladio." The

Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911.

http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11423c.htm

Fletcher.

“Andrea Palladio.” Fletcher, Banister, Sir, G. Bell and Sons, 1 Jan.

1970, https://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/andreapalladioh00flet.

“FUNCTIONAL

ANALYSIS - Villa Capra.” Google Sites, https://sites.google.com/site/palladianvilla/home/1.

Glancey,

Jonathan. “The Life and Legacy of Andrea Palladio, One of the Greatest

Architects Ever.” The Guardian, Guardian News

and Media, 5 Jan. 2009, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2009/jan/05/architect-andrea-palladio.

Hyman,

Isabelle. “Filippo Brunelleschi.” Encyclopædia

Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.,

5 June 2019, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Filippo-Brunelleschi.

Kelly-Gadol,

Joan. “Contribution to Philosophy, Science, and the Arts.” Encyclopædia Britannica Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 5 July 2019, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Leon-Battista-Alberti/Contribution-to-philosophy-science-and-the-arts

Kern,

Chris. “Jefferson's Dome at Monticello.” Jefferson’s Architecture, July 2009, http://www.chriskern.net/essay/jeffersonsDomeAtMonticello.html

Millikin,

Sandra. “Robert Adam.” Encyclopædia

Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 29 June 2019, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Robert-Adam/Furniture-design.

Palladio,

Andrea. The Four Books of Architecture. 1570.

Ware, Isaac: translation 1723. Forward Adam Placzek. Reprinted 1960.

Richardson,

Margaret Ann. “Andrea Palladio.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2019. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Andrea-Palladio.

Ruhling,

Nancy A. “Robert A.M. Stern Architects Creates a University Welcome Center.” Traditional

Building Magazine, 31 July 2019. https://www.traditionalbuilding.com/projects/ramsa-elon-university.

Summerson,

John. “Inigo Jones.” Encyclopædia

Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 11 July 2019, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Inigo-Jones.

The

Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Sebastiano Serlio.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2

Sept. 2019, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Sebastiano-Serlio

“Thomas

Jefferson's Monticello--Presidents: A Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel

Itinerary.” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, https://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/presidents/jefferson_monticello.html.

Wainwright,

Oliver. “A Royal Revolution: Is Prince Charles's Model Village Having the Last Laugh?”

The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 27 Oct. 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/oct/27/poundbury-prince-charles-village-dorset-disneyland-growing-community.

Wilde,

Robert. "Key Dates in Renaissance Philosophy, Politics, Religion, and

Science." ThoughtCo, Oct. 17, 2019, thoughtco.com/renaissance-timeline-4158077.

Wilde,

Robert. "A Guide to Renaissance Humanism." ThoughtCo, Sep. 30, 2019, thoughtco.com/renaissance-humanism-p2-1221781.

No comments:

Post a Comment